Our adventure on Saturday began with a long-sought-after encounter with John Lewis. In the 60’s, John Lewis was one of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. When we heard that (now) Congressman John Lewis was going to be coming to practically all the same sites we were – at the same time – we were hoping we could get to talk with him. We were, after all, huge fans.

Our enthusiasm waned when we realized that there was not a chance we were going to come within a stone’s throw of John Lewis. Or, for that matter, of any of the museums he was in. With the Secret Service everywhere and snipers on the rooftops, we made a few U-turns (of questionable legality) and switched our schedule a bit – since it seemed that Mr. Lewis had stolen our itinerary and copied it word for word.

The Secret Service – not cool, John Lewis.

Once we had switched things up a bit, we ended up at the Rosa Parks museum (sans Secret Service). There was a little re-enactment, as well as a documents from the Montgomery Bus Boycott that went on for a year after Mrs. Parks refused to give up her seat. It was impressive just how humble a woman Rosa Parks was, as well as how well-prepared she was for the crisis: she had taken workshops in nonviolent resistance, she was a secretary for the NAACP, and she was a youth leader. So when she decided she wasn’t going to take it anymore, she knew how to make her simple action into a meaningful protest. Overnight, a woman named JoAnn Robinson initiated a bus boycott that had already been in the making, with Mrs. Parks as the spotlight heroine.

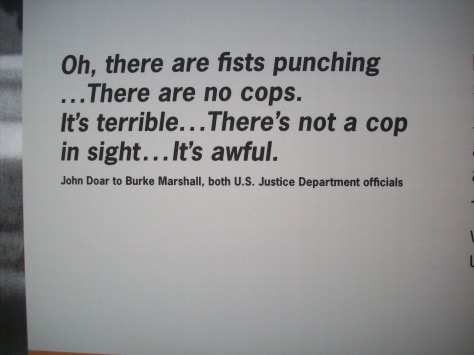

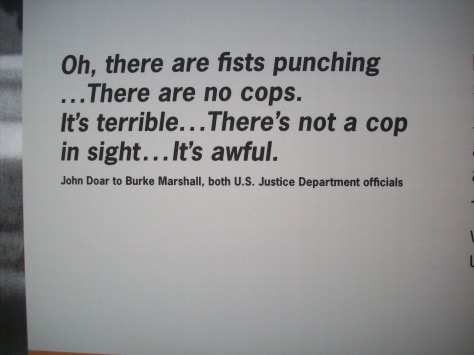

This quote was quite possibly my favorite part of the whole museum.

After visiting Rosa Parks, we went to the Freedom Riders museum. These volunteer riders piled into integrated buses, riding north-south in protest of the southern segregation laws. Upon reaching the South, buses were fire-bombed, and occupants were dragged out, beaten viciously, and jailed. After meeting Catherine Burks Brooks previously, we were all super excited to see more of this story. The museum itself was built in an old, segregated Greyhound station, and the exhibits were largely projects from local artists.

This was the old “colored” entrance to the bus station, bricked in years ago.

We found a picture of our new friend Catherine Burks Brooks!

After the Freedom Riders museum, we stopped for lunch at a local BBQ place. This sign was the highlight, and I consider it the pinnacle of neon achievement:

Beautiful. Just beautiful.

Then we headed to the University of Alabama campus, to meet Reverend Bob Graetz and his wife, Jeannie. The Graetzes were definitely one of the best parts of the trip for most of us; you can only learn so much from a museum exhibit, but you can learn a whole lot from someone who lived through the event itself. Reverend Graetz was the pastor of a Lutheran church in a Negro community just before the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and he told us about his involvement in the Movement. He and his wife helped their congregation by offering and coordinating carpool rides, and their home was bombed by an angry white community. As a white woman, the Graetzes meant something special to me because they provided an example of the white “heroes” of the Movement. It reassured me that not all white people of the era were racist.

Here’s a plug – Reverend Graetz has written a few books, including “A White Preacher’s Memoir” (which I just read – and it is fantastic) and “A White Preacher’s Message on Race And Reconciliation: Based on His Experiences Beginning With the Montgomery Bus Boycott.”

We got to see the house Dr. Martin Luther King and his family lived in while in Montgomery (and I of course forgot to take pictures, so here’s one I kaifed from the internet):

The porch still bears scars from a bombing.

Brother Malden with me and Alexis

And then the Maldens! Nelson Malden was Martin Luther King’s barber, and we got to eat dinner at his and his wife Dean’s house and talk with them about the Movement. Barbershops were a social center of the day, and Brother Malden talked about how Dr. King would come just to sit sometimes and study. (For some reason, I just can’t call these two “Mister” and “Missus”. I automatically call them “Brother” and “Sister” – probably because we sang hymns with them at the end of dinner.) Brother Malden also talked about how much empowerment the bus drivers took from inflicting simple abuse on the black riders.

Sister Malden impressed me (and not just with her cooking.) When one member of our group asked how she kept from hating white people for what they’d done, she looked puzzled and asked for the question to be repeated. After the question was repeated a few times, she said, “Why would anybody hate all white people?” She was honestly stunned that anybody would be angry at the whole population for the actions of a few – or even of a majority. She simply didn’t see the Movement in terms of black and white: it was a matter of treating people like they should be, on an individual basis. ♥

Sister Malden and me